Coronavirus Isn't the First Pandemic in Cal Poly's History — Just The First in 100 Years

As the novel coronavirus sweeps the world, Cal Poly has responded to the pandemic by minimizing the number of people who are physically on campus, while Spring Quarter is continuing online.

It’s a more high-tech landscape than the one that existed more than 100 years ago, when Cal Poly officials had to take drastic actions during the Spanish Flu pandemic — which included closing the campus.

The deadly pandemic reached the Central Coast in October 1918. On Oct. 21, the county’s first flu death was reported, according to the San Luis Obispo Daily Telegram.

By Oct. 26, the county Board of Supervisors passed an ordinance that “makes it unlawful for any person to appear on any street, or in a public place, or any place where people assemble, or where two or more persons are together, except in their gauze mask,” the newspaper reported.

On that day, the statewide death toll stood at 2,500, with more than 60,000 infections reported in California, according to the Telegram.

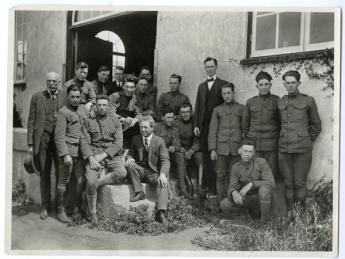

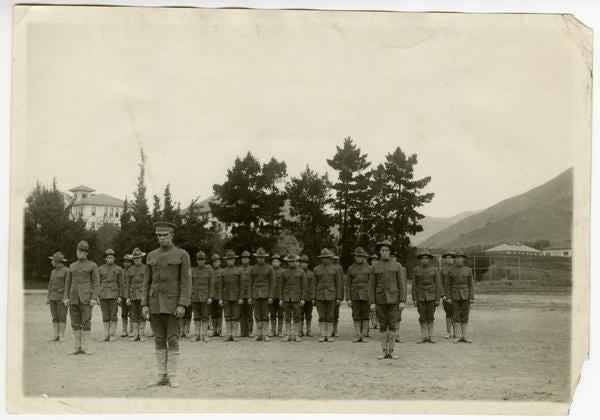

Cal Poly’s Director, Robert Ryder, placed the school under military quarantine in November and December of that year. Students were required to wear masks outside of their rooms and the public was turned away from campus by student cadets.

November issues of the Polygram briefly mention an alumnus who died from the flu, as well as some students recovering from the flu or a severe cold.

The school newspaper notes how relatively insulated the campus has been compared to the rest of the state.

“It is doubtful if many members of the Polytechnic family realize how fortunate this school has been in that it has not been necessary for it to close,” one Nov. 27 article reads. The same article also talks about the inconvenience of the quarantine, but: “We admit that the enforcement of regulations has seemed to do the work.”

Ryder nixed the Thanksgiving holiday and allowed the school to go on Christmas break about a week earlier than planned. The thinking was that if students went home for Thanksgiving, they’d bring the virus back to campus. Instead they’d be gone for three weeks, which would give the virus some time to die out.

That didn’t work quite as planned.

The front page of the Jan. 15, 1919 edition carries the obituaries for a freshman, James Nugent, as well as a teacher, Mary K. Hartzell, both dead of the flu.

One article notes that students and teachers were exposed to the flu when they went home on break.

“Some have not come back, while others have developed the disease since returning to school,” the article said. “Most of the cases are very mild, and so far as known, none is dangerous as yet.”

The article also included this colorful line: “Mr. Redman brought back a case of flu with him as a souvenir of his visit to San Francisco, while Mr. Doxsee has the souvenir without having had the pleasure of the visit.”

The pandemic then forced a five-week closure of Cal Poly’s campus — what the campus newspaper Polygram referred to as an “unavoidable vacation” in its next issue, on Feb. 26.

“Nearly all of the students are back and looking well, not being much worse from the ‘flu,’” the paper said.

The epidemic “wrecked” the school’s athletics according to a March 26 article, which noted that “athletic activities in all the schools have been almost at a standstill for the past few months on account of the ‘flu’ epidemic.”

And the 1919 edition of the Polytechnic Journal noted that, “during the Influenza epidemic everything was dull, as no trips could be taken and no meetings could be held.”

The yearbook also carried obituaries for five people who died of the flu: along with student Nugent and faculty member Hartzell, several former students were listed.

By the time the pandemic concluded in 1919, the virus had killed about 675,000 people in the United States and 50 million around the world, according to the CDC.

There’s no telling when the COVID-19 pandemic will end, but the safety measures Cal Poly has taken this time around echo lessons learned from the past.

Officials have urged students not to return from Spring Break if they've already left town. And campus avoided an “unavoidable vacation” in 2020 thanks to technology, as the campus community continues to learn and support each other virtually.

For more information on the current response to the coronavirus, visit http://coronavirus.calpoly.edu/.