Julia Morgan Exhibition at Cal Poly Shows the Tangible Humanity and Acute Expertise of a Groundbreaking Architect

When the College of Architecture and Environmental Design’s associate dean Mark Cabrinha was a student at Cal Poly, he remembered the dynamic in the college being different. “We were very male dominated,” he said. “I remember so many female students being frustrated and walking out the door. I share that to say that it has flipped. We are more female in architecture than male now and I think that’s phenomenal. It’s something that Julia Morgan probably didn’t see coming, but [she] is certainly part of that.”

Cabrinha’s remarks were only a fraction of the outdoor festivities at the February 4th Gala for “Julia Morgan, Architect: Challenging Convention.” The exhibit was curated by professor of architecture Jennifer Shields, who spoke to the year-and-a-half of preparation leading up to its opening on January 15th. Inside Cal Poly’s Art Gallery, more than a century’s worth of work was on display.

Naturally, the original pieces were by Morgan, but they have been preserved by Cal Poly’s Special Collections Department since 1980. Donated to the university by Morgan’s nephew and heir, the vast body of her personal and professional work highlights what Morgan herself believed was important to save. Additions to the collection were made in the year 2000 by architecture historian Sara Holmes Boutelle, based on her own passionate research. The compilation as a whole is known as the Julia Morgan Papers. Further support for the curation project came from the Hearst Foundation, the Cal Poly Office of Research and Economic Development, and the Cal Poly Scholars program.

Morgan, often mythologized, challenged convention her whole life because of her expertise, determination, and gender. She came of age during a time—at the turn of the 20th Century—when women were essentially absent in her field. In a span of 10 years, Morgan was the only woman to graduate from UC Berkeley with a Civil Engineering degree (1894), was the first woman accepted into the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts architecture program in Paris (1898), and became the first woman to earn an architecture license in California (1904).

It was well documented within the exhibit that Paris was where she grew the most, developing both the stylistic and technological principles of her future craft. According to director of special collections Jessica Holada, her knowledge was only a fraction of her design mastery. “Morgan’s approach to and practice of architecture combined strength, speed, precision, balance, flexibility, endurance, functionality, practicality, grace, artistry, and beauty. In both style and material, Morgan’s signature was her diffused, prodigious versatility. Her designs were also fitting and had presence because they were effective expressions of her client’s wishes.”

In the early 1900s, this multifaceted presence caught the attention of Phoebe Hearst, a bay area philanthropist. She connected Morgan to projects that would promote the public good of the Bay Area, like The Asilomar Center for the YWCA. After Phoebe’s passing, her son William Randolph Hearst retained the expert architect to begin work on Hearst Castle in 1919. Just a 45-minute drive up the coast from Cal Poly, the Ranch at San Simeon was to be the site for a sprawling, luxurious estate. The project would come to be her primary focus until 1947.

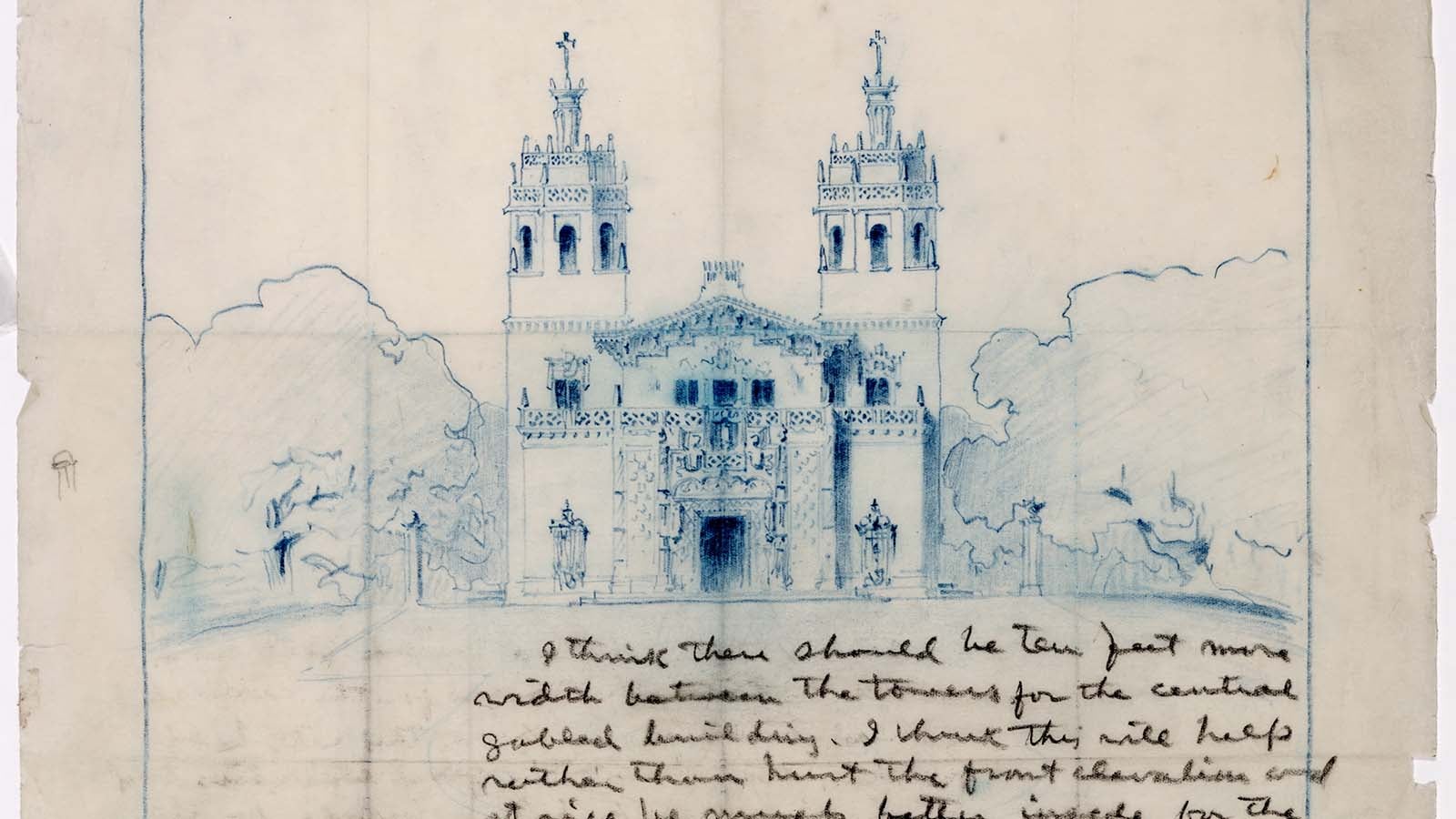

This part of Morgan’s career was brilliantly illuminated by the pieces selected for the exhibition. Several written correspondences between Morgan and Hearst gave a transparent look into their relationship. As shown by the exhibit, the two were in constant discussion regarding cost, adornments, and functionality. And as the project wore on and Hearst’s requests increased in magnitude, Morgan worked tirelessly to fulfill them, always with a client-centric attitude, while upholding her own design convictions.

An example of her work’s surprising scale was a “dramatic centerpiece” of the exhibit, according to Holada. The towering, 17-foot-tall blueprint reproduction called “Canopy on Stair Tower” depicted a potential pillar, including a Medieval style statue of Saint Helen. Professor Shields shared the process for making the artifact accessible to all.

“We couldn’t show the original drawing. But with the help of special collections, we had it conserved, then we had it photographed, digitized, then reprinted on this back-lit material.” Holada, with pride, said “it was worth the effort.” The concept of a to-scale or 1-to-1 blueprint is truly a throwback to another era according to Shields. “We don’t do that anymore. We don’t draw things up full scale today. And that was really powerful—just this giant drawing that would take up most of a studio space.” Although the pillar and statue were never brought to life, the blueprint is a window into the decades of behind-the-scenes work that built Hearst Castle.

The design of the rest of the exhibition guided the viewer through a cohesive, yet wide-ranging collection of pieces. Since the Julia Morgan Papers are primarily from her former residence in Monterey, CA, the exhibit had an intimate tone. In some areas, it felt like the viewer could have been a guest in Morgan’s home.

This was perhaps most true near the entrance of the space, where her wooden drafting table was staged. Indelible ink and paint marks reminded the viewer that she was committed to architecture and design even away from the site. So little of the work we do today—not only due to the pandemic, but also because of society-wide digitization—will be realized in a physical way. There are increasingly fewer elements of daily life that we can touch, hold, and run our hands over. Examining her desk gave visitors a chance to look back at a more tangible era.

Another eye-catching piece at the exhibit was an ad targeted at homemakers, which had been torn out of the Saturday Evening Post. Miniature architecture sketches dotted the margins. To Shields, the irony was palpable. “That juxtaposition to me was really interesting—that she kept a page of a magazine that had a couple of rough sketches on it. What made her keep that sketch?”

Shields left it up to the viewer to come up with their own interpretation. Like Julia Morgan’s process, the majority of the work for the exhibition was preparatory. Several student assistants worked hands-on throughout the whole operation, including Munira Aliesa, a fifth year Architecture major. “I started with Professor Shields at the very beginning. My initial job was assisting with taking the artifacts that [she] and Special Collections at Kennedy Library had compiled for the Virtual Exhibit and uploading them.” (Although the physical Exhibit is now closed, the Virtual Gallery is available until April 30th.)

Professor Shields then moved Aliesa into the physical space, designing posters and didactic panels which would educate visitors on the various artifacts. She also played a role in the overall design of the exhibit. “That was really nice. That’s where I had a little creativity. We did some research on precedents of gallery layouts, looking at the flow of how users entered, what artifacts they would see, and how to group the artifacts. We decided on specific zones based on the time periods of the artifacts that we had.” Because of Aliesa’s and many other student assistants’ contributions, the exhibit flowed seamlessly between pieces, providing an educational and insightful look into Morgan’s career.

The exhibition aimed to change convention in a small way, as its subject did in a big way her entire career. “Everyone knows Julia Morgan because of Hearst Castle. But it always seems as if the prevailing importance is placed on Hearst,” Aliesa said. “I think everyone needs to recognize that most of the work was actually done by Julia Morgan herself.” According to Holada, she was “like a world-class gymnast who excelled in all the events.”

At the gala, Shields mentioned the possibility for the exhibit to travel. UC Santa Barbara and a gallery in San Francisco have expressed interest in displaying the Julia Morgan Papers, a one-of-a-kind humanizing collection. Although her impact may be much larger than her life, “Julia Morgan, Architect: Challenging Convention” portrayed her as she would’ve wanted: a passionate, highly skilled, and innovative architect.