A Recipe for Revitalization: How One Student is Helping Preserve Indigenous Food and Language

When Cheryl Flores sat in her first ethnic studies classes at Cal Poly, she wasn’t thinking about her future — she was thinking about her family’s past.

Flores, who descends from the Wixárika people of Mexico, recalled the childhood stories her father often told. He was shamed for speaking Spanish in school — put in a corner with paper and crayons until he learned English. He vowed to never teach his children to speak Spanish, even though Flores herself was teased for not speaking the language in the Latino community where she was raised.

Though Flores said she initially resented her father for severing that linguistic tie, she eventually began to see her family’s story as an example of acculturation.

Acculturation is the process of assimilation into another culture. In North America, Native people have experienced acculturation through well-documented oppression, brutal colonization, boarding schools and government programs designed to erase Indigenous culture, including Indigenous languages.

In fact, most of the roughly 200 North American Indian languages spoken in the U.S. and Canada today are facing extinction — a statistic Flores cited during the State of Indigeneity event in November. Many of those languages are spoken by fewer than a dozen people — or are only spoken by elders — and they may not survive the next century.

“With the risk of linguistic extinction comes the risk of losing centuries of information, traditional knowledge, understanding of land around us, and the ability for culture and traditions to be fully passed forward to future generations,” she said during the virtual gathering, citing her father’s experience as an example.

Following Flores’ epiphany about her own family’s place in this history, she began making more phone calls home and having frank conversations with her grandparents and her 15 aunts and uncles. To break the ice, she started with questions about their favorite homecooked meals. From the hazy recollections of family traditions to more painful memories that had never been shared before, Flores began seeing the full picture of how assimilation was extinguishing her family’s culture.

“I'm the only person who can change that narrative,” said Flores. “And I remember calling my dad and letting him know, ‘This is actually part of our history — unfortunately, we just don't learn it in school.’”

Now her family’s experiences — the beautiful, the difficult, and the delicious — have become the centerpiece of Flores’ senior project, titled “Erased: Growing up Brown in the United States.” The work focuses on the process of acculturation and the effect it has on families, including parts of their culture that have been lost.

“I realized that a lot of our dishes have disappeared — they're gone,” she said after her discussions with family members. “What I've done is I've written down their dishes that they remember, and at the end of my project, I’m going to create a cookbook for each side of my family.” So far, she’s gathered 22 recipes from her mother’s side and is actively working on dishes on her father’s side.

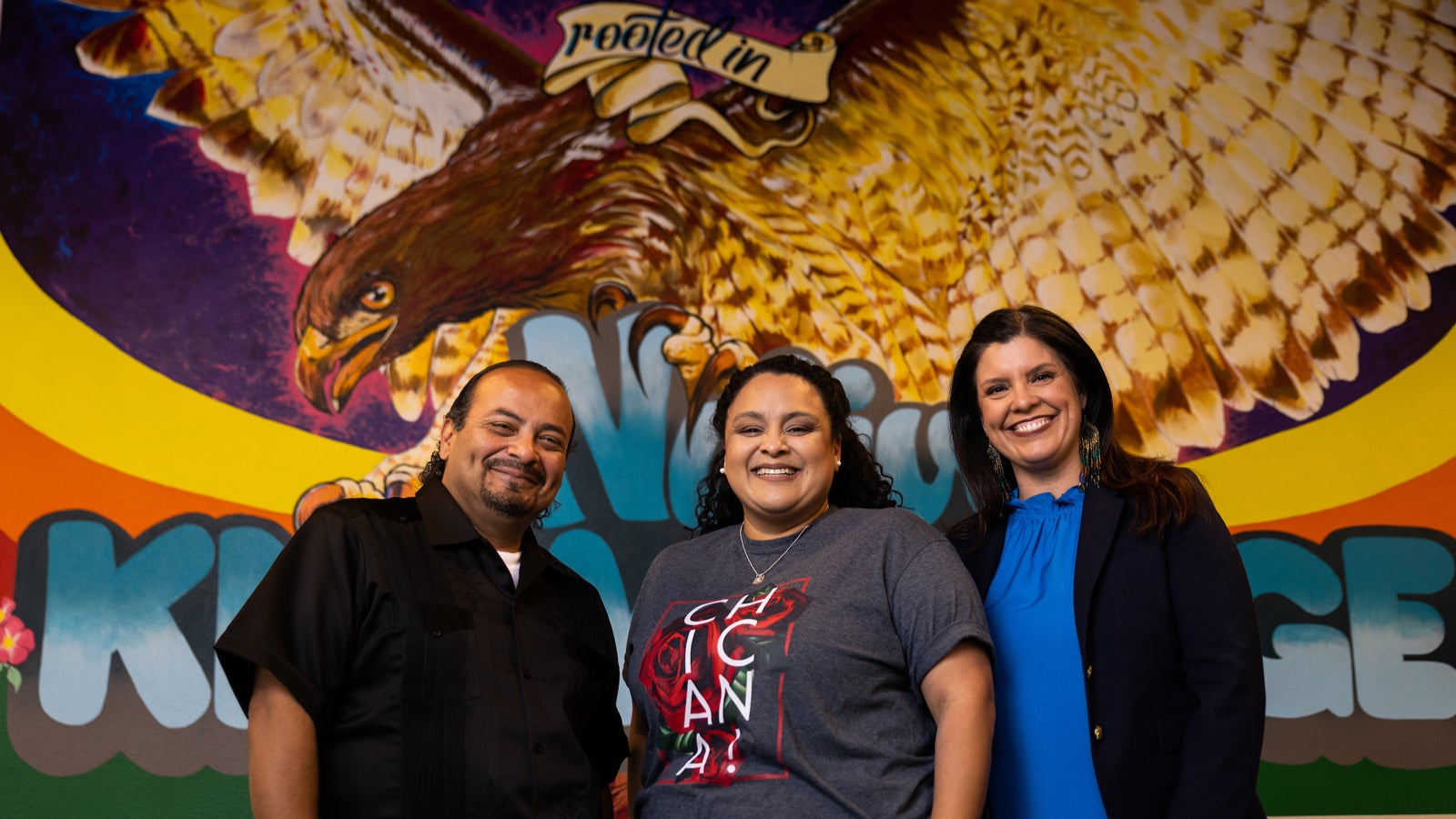

“She is incredibly enthusiastic and passionate about the work that she's doing,” said Jenell Navarro, chair of the Ethnic Studies Department, of Flores’ advocacy. “She is unapologetic about the revitalization of her own family’s Indigenous identity and food practices. At a predominantly white institution, she has found a way to assert that this is also a space in which she belongs — she is a scholar in her own right.”

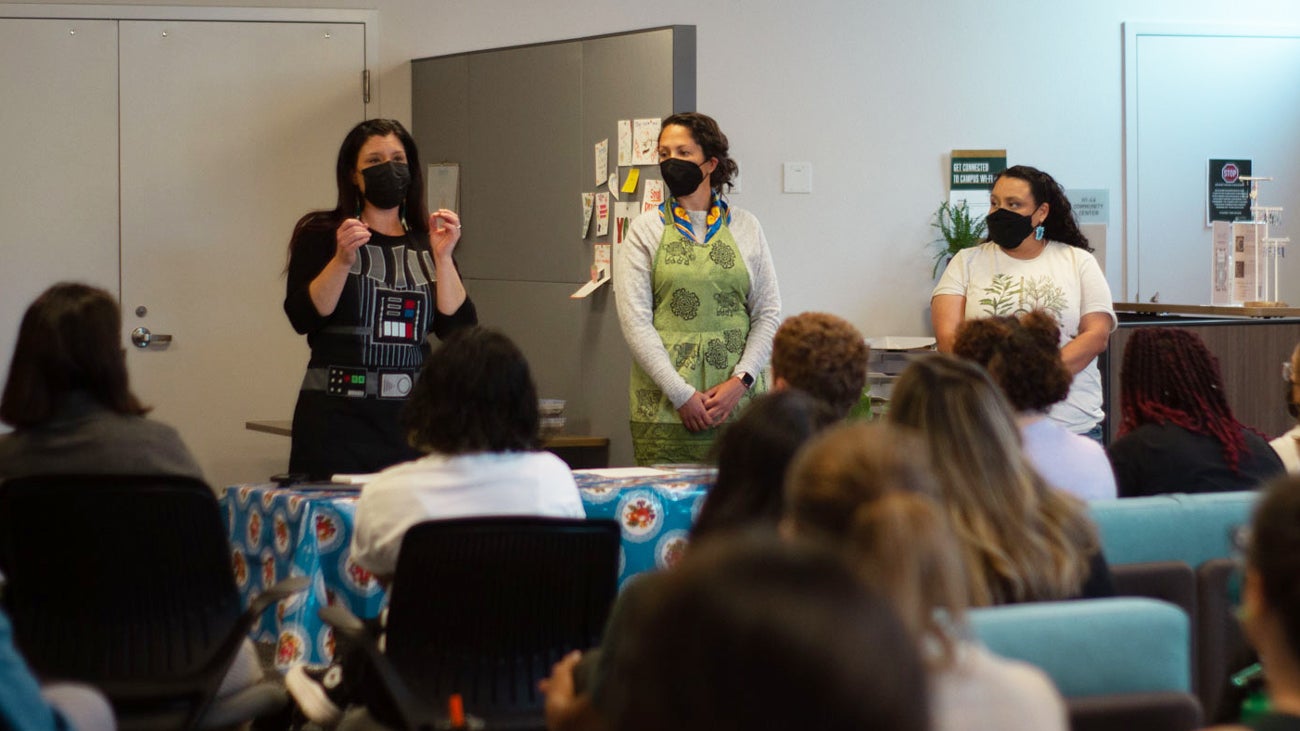

In February, Flores teamed up with Navarro and Professor Lydia Heberling to bring some of those Native recipes to campus. The trio gave a presentation called “The Indigenous Kitchen: Stories and Recipes for Healing and Wellness,” during the university’s annual Social Justice Teach-In.

In front of a packed house at the Native American and Indigenous Cultural Center (NAICC), the group shared the history of staple ingredients essential to their Indigenous communities and anecdotes about how they have experienced different dishes. Each attendee enjoyed a box filled with samples of blue corn cookies, wild rice cakes with raspberry and rose hip syrup, crab salad and bison jerky.

As Navarro discussed the significance of blue corn and Ojibwe wild rice, she advocated for food sovereignty, where Indigenous communities would be able to earn money by defining their own agricultural systems on their homelands. Flores proudly prepared a salad with nopales, leaves from a cactus like the one that grew in her grandmother’s garden. Flores’ grandmother spent time with Cheryl in the garden teaching her the story of each plant and its uses before she passed away.

“She left me with culturally accumulated ecological knowledge,” Flores explained as she handed out recipe cards to the audience. “I want to make sure you know that in order to keep that going, you need to have those conversations, sitting down at the table, making that phone call or just by writing down that recipe. It’s through you that that knowledge is going to pass down to future generations.”

In addition to speaking at educational events, Flores has also distilled her family’s stories through poetry. She penned “A Box of Crayons” about her father’s painful experiences in school, and “Nopales” about the cactus’ overlooked resilience. Though they are so personal — and at times difficult to read — she hopes to share them at Cal Poly’s OWN (Original Womxn’s Narratives) storytelling event.

While Flores has spoken a lot about what has been lost, but she’s just as passionate about what can be found when all students feel supported.

After transferring to Cal Poly from Cuesta College, Flores quickly galvanized the student community through the Comparative Ethnic Studies Student Association, where she served as an officer, and as a student assistant in the NAICC. Navarro says Flores has gone above and beyond to lead the center: helping paint the center’s mural, planning grand opening events with Tribal Elders and the campus community, creating a food pantry for students, and advocating for more university outreach to Native communities.

Professors Jenell and José Navarro have mentored Flores through her time at Cal Poly and have watched her become an academic leader in the Ethnic Studies cohort. But they say they’ve learned from her as well, and their friendship will endure long past graduation.

“There are always a handful of students for me who are like family members, and even from an Indigenous framework, I understand them as relatives,” said Jenell Navarro. “Cheryl is one of those students who I see as a family member.”

Now Flores has set her sights on Cal Poly’s Master of Arts in Educational Leadership and Administration program. As a person of color and a member of the queer community, she wants to help other students who many not see their identities reflected around them.

“I want to give back to my community what I wasn't given. Being a first-generation student, it was hard to know the system, and I want to be that person that somebody sees when they walk onto campus and they see themselves in me.”

Want more Learn by Doing stories in your life? Sign up for our monthly newsletter, the Cal Poly News Recap!