Shoot for the Moon: Engineering Students Showcase Prototypes at NASA Challenge

By the time NASA’s Artemis II mission flies to the moon, some of the tools they’ll be using to ensure a successful mission could come from tech developed by Cal Poly students.

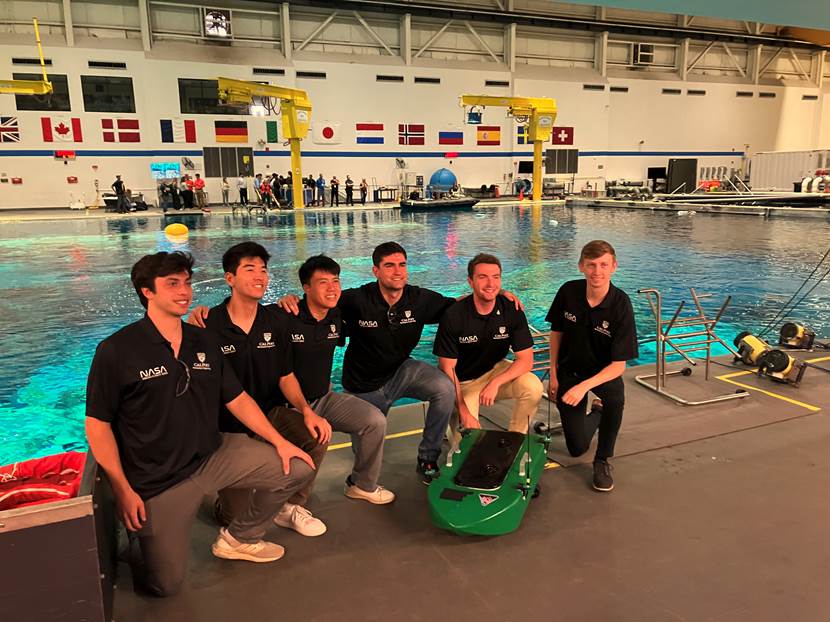

In early June, two teams of engineering students flew to Houston to compete in NASA’s Micro-g NExT (Neutral Buoyancy Experiment Design Teams) Challenge. The challenge invites student teams from around the country to design, build and test a tool or device that addresses a current challenge in space exploration.

The students present their projects at Johnson Space Center, where NASA staff test them under student direction. NASA doesn’t pick a winner — instead, they learn from all the prototypes as they develop solutions for future missions.

And one of the missions students could contribute to has a Mustang connection: astronaut and alumnus Victor Glover, who will be part of the Artemis II mission.

There are four categories that students can work within: astronaut training, International Space Station, Orion crew safety and lunar surface operations, with a specific project assigned under each category. Cal Poly’s teams worked on projects in the Orion crew safety and lunar surface operations categories.

The crew safety team created a surface autonomous vehicle for emergency response (SAVER), which would be used in the event of a failed launch. During a rocket launch, it’s too dangerous to put a crewed boat near the launch site, so an autonomous vehicle like this could act as a first response and possibly rescue the Artemis crew if something goes wrong.

“The goal of the USV (unmanned surface vehicle) is to identify the hazards in the area, if any, so that search and rescue personnel can make informed decisions about how to retrieve the astronauts safely and to quickly provide resources to astronauts in the meantime,” said Addison Sandvik, an electrical engineering graduate student who’s been working on Cal Poly’s SAVER project since it started in September. “This device could also be used anytime astronauts end up in the ocean, including after the astronauts return to Earth from space.”

Sandvik, who was a fourth-year computer engineering student when the project began, worked with his team to modify existing software for the direction-finding system for the vehicle’s navigation system.

“That was my first experience of looking at somebody else’s code and making it do what I wanted,” he said.

Sandvik and the rest of his team’s hard work paid off: when they tested their device at the Johnson Space Center, it was the first boat to successfully reach the rescue beacon in three years of the competition.

“What we make definitely won’t be in the water on launch day, but what we do could give design ideas to NASA engineers,” Sandvik said.

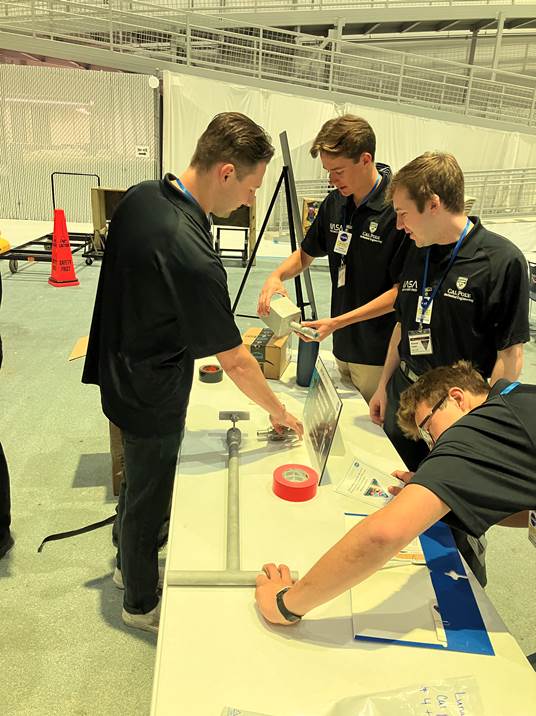

The lunar surface operations team reviewed logs from the Apollo missions as they designed and built their prototype for a dust tolerant extension handle mechanism.

When astronauts go to the moon, they need a lot of lunar sample collection tools in the smallest form possible. An extension handle helps astronauts switch between collection tools more easily. These mechanisms were previously used the last time humans went to the moon, 50 years ago — and the dust proved difficult to deal with.

“Lunar dust is super harsh and abrasive,” said Dylan Weiglein, a fourth-year mechanical engineering student who worked on the project as his senior project. “The reason this project exists is because the mechanism that they used on the Apollo missions kept getting jammed up by the lunar dust.”

There are two options for dealing with the dust, according to team member Andrew Reese.

“The first would be making your design so tight that it’s impossible for dust to get into the mechanism. But we went the other route,” said Reese, a mechanical engineering student. “We can’t do anything about the dust, so let’s take a very open approach where no matter how much dust gets into our device, it’s still going to work.”

At the challenge, the mechanism received high marks for ease of use and functionality from both the diver who tested the device in a simulated microgravity environment and during the lunar dust simulant test.

Mechanical engineering professor Peter Schuster, who advised both teams, said his students performed well during the stress of testing, documenting results and making any necessary adjustments on the fly. Not only did they support each other, but they also worked well with other participating teams, he said.

“I was proud to see how well they represented Cal Poly, both through their prototypes’ success and their interactions with others,” Schuster said.

Reese, who also worked on the prototype as his senior project, said the experience has helped him narrow down industries he is passionate about.

“This challenge showed me that no matter what steps I take when I start my career path, I now know one area that gets me excited,” he said.

Weiglein added that this was their first experience with the engineering design process starting from scratch and seeing it through to the finished product.

“It definitely gave us a lot of insight into how projects like this work, what your expectations should be for lead times, and finding the best ideation and manufacturing strategies,” Weiglein said.

Before the teams flew to Houston, Reese told Cal Poly News that he was honored to participate in engineering work on one of the most historic campuses in American space exploration.

“We’re going to be bringing our ideas to a place where some of humanity’s greatest ideas have been conceptualized and born,” Reese said. “I’m still just shocked that my Cal Poly education has provided me an opportunity like that.”

Want more Learn by Doing stories in your life? Sign up for our monthly newsletter, the Cal Poly News Recap!