Student Pilots Program to Help Professors, Students Talk About Racial, Social Injustice in Engineering

When Biomedical Engineering professor Trevor Cardinal gave the students in his engineering physiology class their first lab of the fall quarter, it was different than usual — and not just because he was teaching his class over Zoom.

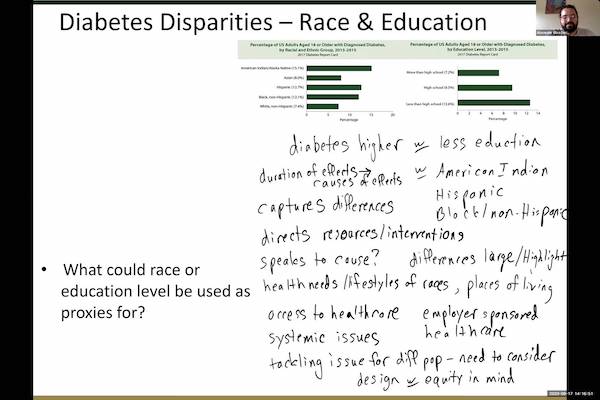

During the lab, the students used inexpensive glucometers so they could measure their blood glucose and infer what was happening with their insulin levels. Cardinal and his class talked about how cells communicate with each other, and then they talked about another subject pertinent to the lab: the racial inequities present in diabetes cases.

“There are clear but sad disparities among Hispanic, Black and Native American populations in terms of diabetes instances and treatments — what’s offered to different groups seems to stratify based on race,” Cardinal said.

This quarter, Cardinal and his class were a test group for a new program that works with faculty to open up discussions on racial inequities and injustice within their class topics.

The program is the brainchild of Alexander Silva, a master’s student in biomedical engineering who completed their undergraduate coursework in the spring. Silva got the idea during their final undergraduate quarter, after they took a biomedical engineering class that focused on maternal health issues and looked at engineering through the lens of gender and sex.

“It was the first engineering class I had where we intentionally had a conversation about race and racism and how it relates to engineering,” Silva said. “As a student of color, that was one of the most meaningful conversations I’ve had.”

A conversation with the lecturer who taught the class, Sara Della Ripa, spurred Silva to send a list of helpful resources on inclusivity and equity to biomedical engineering faculty. Three professors, Trevor Cardinal, department chair Lily Laiho, and Jamey Eason, reached back out to Silva in support.

Cardinal noted that the death of George Floyd and subsequent protests across the country awakened an urgent need to do something about discrimination and inequality. Given his role as a professor, educating students on these topics seemed like the best place to start.

“It’s the kind of conversations students want to have but everyone’s a little nervous about having,” said Eason. “As faculty, we’re not really trained to bring up sensitive topics: some students may be more emotional about it, and other students may be more callous, and that’s not something we’re good at dealing with as scientists.”

With input from Silva and Cardinal, Eason drafted the proposal for — and won — an IDEAS grant through the College of Engineering, which gave Silva funding to do in-depth research on how to bring topics including racial injustice and inequality into biomedical engineering classes.

“How do we bring these conversations into engineering where it makes the most sense, and how do we introduce these concepts in the classroom?” Silva said. “A lot of people don’t associate science with these conversations. We can still be scientific but with social applications.”

Throughout the summer, Silva was hard at work researching resources and coming up with a facilitator guide for professors. They met regularly with Cardinal, Eason and Laiho, who listened to their findings and gave them feedback.

Cardinal’s class was picked because the existing lecture content allowed for the seamless incorporation of clinical data to drive discussions on racial inequality and injustice in medicine, which gave Silva more of a chance to closely observe and help facilitate the three discussions that took place throughout the quarter. They also surveyed the students before and after the first activity to gauge their comfort level and the importance they placed on having conversations about racial injustice and equity.

“The most surprising part was that students rated themselves as being comfortable having these conversations, and after the activity a majority of students were saying ‘I don’t understand why we don’t have these conversations more,’ and I resonated with that,” Silva said. “They hadn’t really had the chance to have these conversations in an engineering-specific setting.”

Right now, Silva is trying to lay the foundation to integrate more frequent conversations about racial justice and equality in the classroom, with the hope that it will encourage professors and students alike to think about racial and social justice outside the context of a single lecture or a specific ethics class. They are hoping to expand into other classes as well.

Laiho, the department chair, supports that vision.

“It’s not just a one-time thing and it’s not to check a box. These are really important issues,” she said. “This is something that people need to be aware of. I think it’s easy to go through life with blinders on and think ‘It works for me, so everything must be great’ and that’s not the case. [Having these conversations] makes us more empathetic.”

Silva hopes that the guidelines can help professors facilitate conversations that encourage students to listen to each other, respond respectfully and think about the consequences of inequity in an engineering context. They also hope it can show other engineering students of color that their perspectives and life experiences outside of the classroom are valuable.

“I want people to know that you can be accepted, and you can bring your whole, authentic, genuine self to engineering,” Silva said. “Even if you don’t know the technical information of some of your peers, I hope you can find value in yourself as an engineer, and as the person that you are.”

“This work has huge ramifications for marginalized and underrepresented communities as engineers need to be socially-minded and socially aware,” Silva said. “By including these topics and conversations, we can actually make changes. We’re the ones who are supposed to make the world a better place, so let’s make it a better place for everyone.”