Cal Poly Students Practice Physics with Phones and AI

Ever wonder how jittery consuming a can of energy drink or cup of coffee will make you? Or how much distance you cover with your natural gait?

The answers are as close as your cell phone.

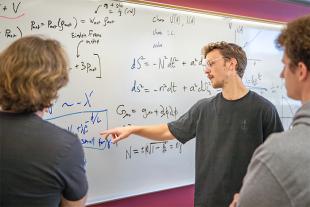

For the first time in a full series of labs at Cal Poly, students are using smartphones and an innovative physics curriculum to collect and record data related to motion, force, energy, pressure, velocity and other physical actions.

Physics Department Chair Jennifer Klay collaborated last fall with David Rakestraw, a senior scientist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in the Bay Area, to launch his Physics with Phones curriculum at Cal Poly.

The free curriculum merges technology, biology and physics in a Physics 125 course, an introductory lab required for pre-healthcare and pre-veterinarian students. The use of the innovative smartphone curriculum has been adopted on an ongoing basis, Klay said.

Rakestraw has developed hundreds of physics experiments for smartphones as well as a guide to performing them. Physics with Phones lesson plans and related artificial intelligence, or AI, applications are being applied in hundreds of high school classrooms and dozens of colleges globally since 2020. As word spreads about the resource, educators at other campuses are considering ways to introduce smartphone instruction into even more classrooms.

Klay said that using smartphones saves schools money while reaching and engaging even more students on a device they are familiar with.

“Researchers spend hundreds of thousands of dollars for equipment in very controlled lab settings,” she said. “Physics using phones can achieve the same results — even better calculations in some cases — and help innovate.”

Cal Poly students have been using the new curriculum in experiments to measure changes in hand tremors before and after consuming energy drinks. In addition, they have learned to assess walking distances based on foot motions and angles, lessons with applications in healthcare and veterinary science, Klay said.

“I was extremely interested in the way our phones were integrated into our physics laboratory,” said Zane Sieger, a fourth-year biological sciences major and pre-medical student, from San Diego. “I think we severely underestimate the amount of technology and physics that our phones use. I believe that other Cal Poly students will enjoy coming into lab each week and integrating a device so familiar to us as I did.”

Biological sciences major Adia Pinski, also a pre-med student, from Kirkland, Washington, agreed.

“This experience not only deepened my understanding of physics concepts but also highlighted how mobile technology is transforming the way we conduct experiments, making science more interactive and accessible,” she said.

Androids, iPhones and tablets are built with powerful sensors to support applications for navigation, gaming, photography, talking and listening to music. These sensors include accelerometers, gyroscopes, pressure transducers, microphones, light detectors, speakers and GPS sensors commonly used in physics.

Lab activities are designed so that each student is responsible for individual measurements with his or her own smartphone or a class loaner.

Free smart phone apps that are available to anyone, such as the physics-focused phyphox developed by physicists at RWTH Aachen University, a top public research institution in Germany, which allows data to be exported in common formats such as Excel or CSV files, a plain text format that stores data in a table-like structure.

Besides physics, which will continue to use the phone-related curriculum at Cal Poly, other disciplines such as kinesiology and engineering may incorporate the technology in the classroom.

Additionally, Klay and Rakestraw are collaborating to apply AI (Chat GPT) to calculate complex sets of data, recorded by phones, that otherwise would be too challenging for early-stage physics students to do on their own.

“We were able to use AI to write a natural language prompt to do an analysis that otherwise would be too complex for an introductory physics lab,” Klay said. “The same algorithm is taught in the third-year physics curriculum, or beyond, and in the electrical engineering curriculum. We can use this technology to educate novice students without overwhelming them.”

Rakestraw added: “Students really learn about science and engineering not just by being lectured to and solving problems in the back of the book, but by really being involved in experimental investigations and hands-on learning.”

Want more Learn by Doing stories in your life? Sign up for our monthly newsletter, the Cal Poly News Recap!