Why is the Universe So Big? Research Teams Tackle Astronomical Questions

Wrestling with the mysteries of the universe that intrigued Albert Einstein and have perplexed other prominent theoretical physicists for generations is the mission of a student team working with physics professor Ben Shlaer.

Shlaer is the recipient of the 2024-25 Astronomy Faculty Research Fellowship, supported by the Marrujo Foundation, established by Cal Poly alumnus Dan Marrujo (Electrical Engineering `08) and his wife, Rosamaria Marrujo.

Shlaer is working with multiple teams of students and former students on investigations into the unknowns of space and time — and abstract questions around early universe cosmology relating to the big bang, black holes and universe expansion.

They are taking on fundamental questions about the universe such as: Why is the universe so big? Did the universe start with a singular big bang out of nothing? Or was it a bounce that involves a cycle of expansion and collapse after the universe emerged from a prior universe that collapsed until it became extremely dense? Can these mysteries be explained under the time-reversal model that envisions an ongoing expansion and collapse of the universe?

“The questions we’re trying to answer are still being asked in the field,” said Josiah Hauck, a fourth-year physics major. “I’ve always been interested in cosmology and black holes and the point at which physics kind of breaks and requires a deeper level of understanding to solve. That’s very exciting.

“As an undergraduate researcher, our study is a great opportunity, even if it can be hard to conceptualize. I want to develop the skills of being able to approach a problem from a more theoretical approach.”

Another physics student, Aaron Whorl, said that he has enjoyed the challenge of the studies, which can require a different type of thinking.

“This is not typically undergraduate level work. It’s often done in graduate school and other higher levels of research,” Whorl said. ”This research challenges a different part of your brain that you have to engage. It started with a lot of self-study. And Dr. Shlaer would send us academic journal papers to learn about this field.”

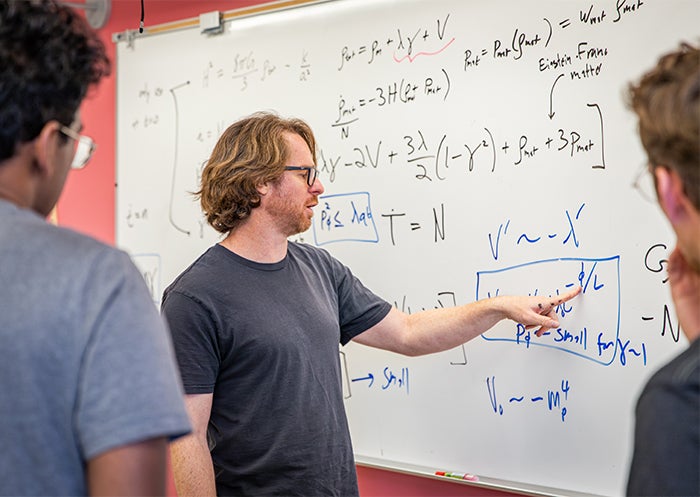

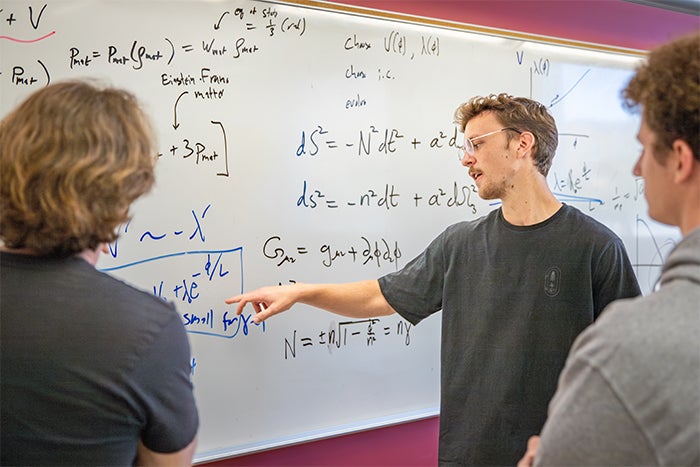

In a recent team meeting, the students and Shlaer collaborated on a full whiteboard of formulas, testing theories and calculations that strive to prove and disprove models to answer cosmology questions.

“There’s no natural understanding of initial conditions of the universe,” Shlaer said. “All of the physics we’ve ever developed is really a theory of how to predict what happens from certain initial conditions.”

Shlaer and his current students are trying to sidestep the thorny issue of the universe’s initial conditions by basing their work on a model that predicts that time must flow backwards and forwards, and almost all motions can be reversed.

“By allowing for time, as perceived by gravity, to not always be increasing, but to decrease and then increase, that mimics the possibility of a collapsing universe that then re-expands,” Shlaer said. “But the mechanism that causes the universe to expand, and to produce the big bang, is that time itself is what’s reversing.”

Shlaer plans to publish three separate academic journal articles to contribute to the scientific community in coming months.

One involves three current physics majors (Hauck, Whorl and Sanjay Sreejith), tackling questions around whether a time-reversal model can explain dark energy, or the mysterious force that causes the observed accelerated expansion of our universe, in a more natural way than other theories.

Shlaer’s work also involves two other planned publications with recent Cal Poly graduates. One proposes what could be called an explanation for the Big Bang; another team is using the model to investigate the interior structure of black holes. These objects aren’t really holes; instead they are massive concentrations of matter packed so dense that gravity just beneath its surface, the event horizon, is strong enough to keep even light from escaping.

Shlaer’s teams apply a model of “non-singular general relativity,” a modification of gravity that doesn't have singularities, or the point in time where gravity is so intense that it breaks down space-time catastrophically and the density of matter becomes infinite.

Sreejith, who had an interest in string theory (a theoretical concept in which the pointy particles of particle physics are substituted by one-dimensional objects called strings), took Shlaer’s Introduction to Physics Research class last year and became drawn to the mind-boggling field of study.

“I wasn’t specifically thinking of doing this kind of research, but I went to talk to Dr. Shlaer and got involved,” said Sreejith, a third-year physics major. “We’ve been working steadily on these studies ever since.”

Whorl said it will be an honor to publish scientific journal articles as an undergraduate.

Shlaer added: “Thanks to the Marrujo Foundation, we expect to finish all three of these projects during winter and spring quarters, and to submit three manuscripts to journals for publication by the end of the academic year (roughly one per quarter). I’m thrilled our students have to opportunity to be part of this work to do high level research as undergraduates.”

Want more Learn by Doing stories in your life? Sign up for our monthly newsletter, the Cal Poly News Recap!